The Brunswick Telegraph said it best: Samuel Randall Jackson “was the architect of his own fortunes.”

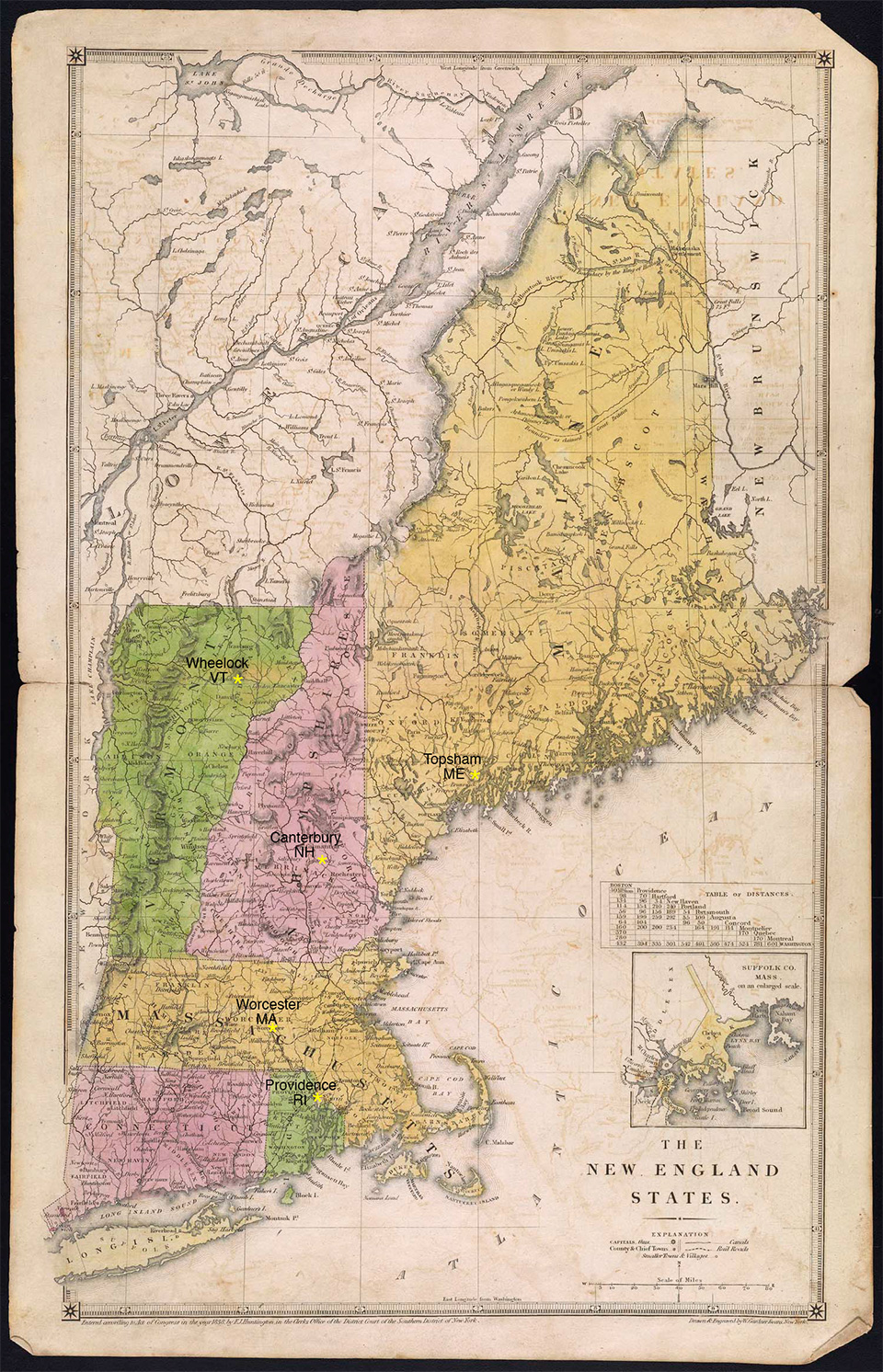

Born in New Hampshire in 1803, then raised on a small Vermont farm, Samuel realized early that rural life wasn’t for him. So at age thirteen he left home to make his own way in the world. Thus began the pattern of his life: embrace adventure, work hard, and when hardships come, begin again.

Somehow he arrived in Topsham, Maine, where he worked his way up from chore-boy in a factory to clerk in a local store. By age twenty-one, Samuel owned a store of his own. Life wasn’t always smooth sailing, though. Twice in those early years, he lost everything. The first time was when the shop he worked in burned to the ground. The second was when the store he owned went up in flames. After each misfortune, Samuel began anew.

During his years as a Topsham merchant, he made the acquaintance of Jane Fulton Winchell (1808-1889). Jane had suffered her own personal tragedies when Samuel first came to town. First her mother, then her father died, leaving Jane and her ten siblings orphaned. Somehow she and her family struggled through. When her youngest sibling reached adulthood, Jane and Samuel married, having known one another almost fifteen years.

They settled in Worcester, Mass., where Samuel learned the lumber business. Their family soon grew to include two daughters and one son.

The Jacksons, it seems, had strong ideals from which they refused to waver. Samuel was an abolitionist, disapproved of capital punishment, and supported women’s rights. When he and Jane learned their Methodist Episcopal church didn’t share their anti-slavery view, they seceded from it to join a more liberal Wesleyan Methodist church.

Their ideals must have included self-determination for Native Americans, for they named their son Osceola, after the Seminole warrior who refused to sign a treaty that would have given Florida tribal land to the United States government.

Samuel, ever striving to learn and advance, became superintendent of the Providence and Worcester Canal. In those days, traveling over land was a difficult and time-consuming business. The canal was an easier and quicker way for manufacturers to transport goods to rural areas, and for farmers to send produce to the cities. In the 1840s, though, the new railroads provided even faster means of travel, forcing the canal to close. Samuel simply began once more, this time returning to his merchant roots. Perhaps remembering the Topsham fires, he started the Jackson and Clark Coal Co. to sell the safer–and very profitable–fuel.

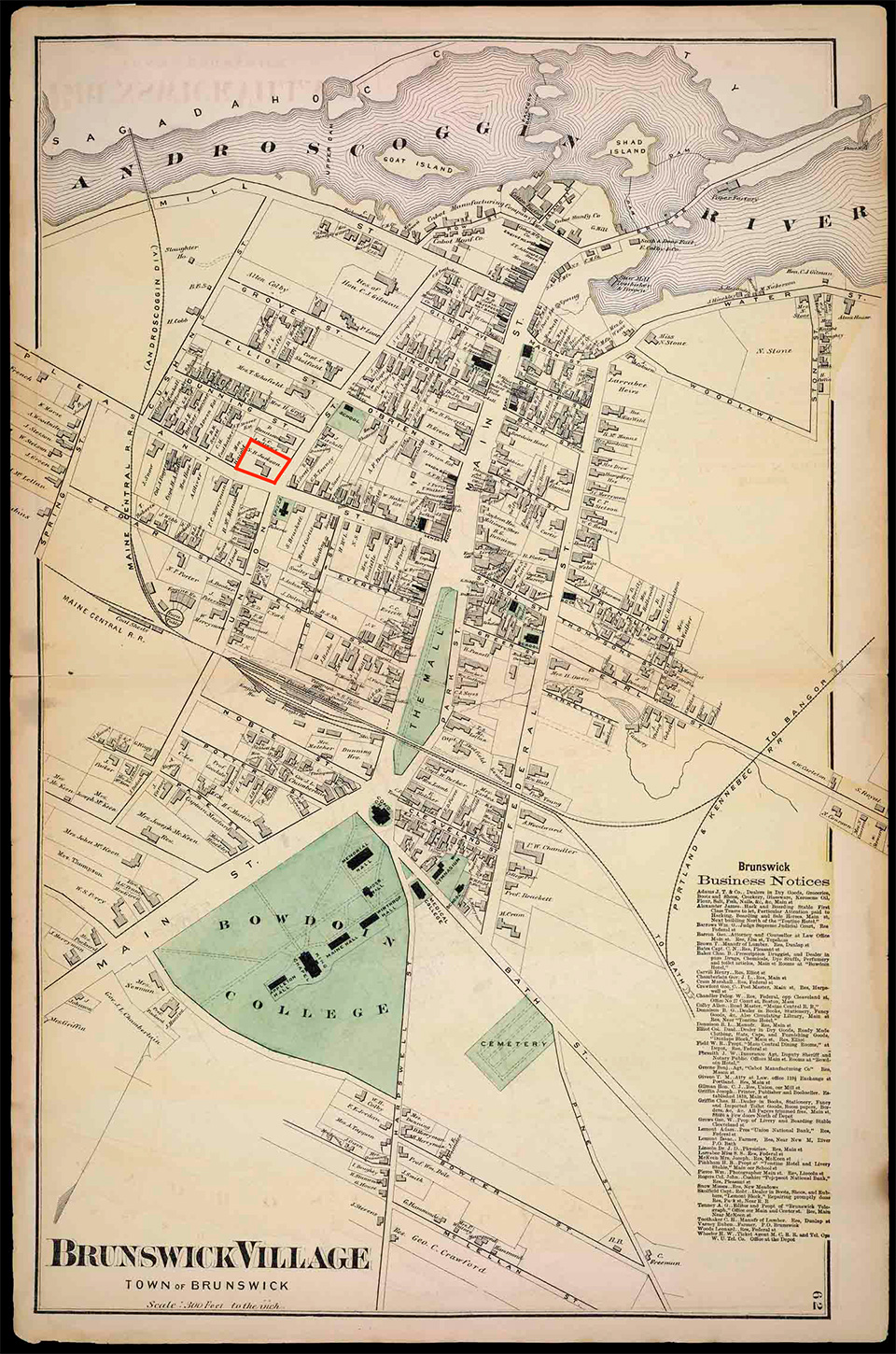

When gold was discovered on the west coast, he saw another opportunity for profit. In 1850, Samuel left New England for the boomtowns in California and Oregon. He didn’t go as a miner, though, but as a coal merchant. But before he left, he resettled his family in Jane’s hometown in Maine to await his return.

It would be another two years before his family learned that Samuel’s adventure had left them to begin again.